This week, I have been privileged to stand before many great works of art.

The British Museum is famous (infamous, some say) for its collection of marbles known as “the Elgin Marbles.” Lord Elgin visited Greece while he was ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1801 to 1805, and was appalled at the condition of the marble statues on the Parthenon. The Parthenon was begun around 447BCE, under the supervision of the architect and sculptor Phidias.

The marbles had been damaged in 1687CE when the Parthenon was bombarded and the ordnance stored inside exploded, causing much of it to collapse, and the remaining portions of the building and its sculptures were also subject to vandalism (for example, two heads had been removed from one of the metopes by a Danish officer, leaving just blank space behind).

When Elgin visited Greece it was occupied by the Ottoman Empire, and Elgin claimed to have obtained permission from the Ottoman government to remove the sculptures under the pediments at each end of the building, parts of the frieze which ran around the outside of the building and many of the metopes, which were located above the columns in the second row. He also removed one of the ‘caryatids’ from the Erechtheion porch.

All of the Parthenon marbles are displayed at the British Museum in a special hall built simply for their display, and I stood in awe before them and wondered at their artistry, and their state of preservation.

The frieze showed a procession including a heifer being led to be offered as a sacrifice. This picture shows the exquisite detail of the carvings, and also the damage that it had endured over the 2,000 years since its carving

Another portion of the frieze shows horses and their riders. They were riding 4 abreast, and it’s hard to understand how the artist could have kept track of what portions of each horse belonged in each plane of the carving:

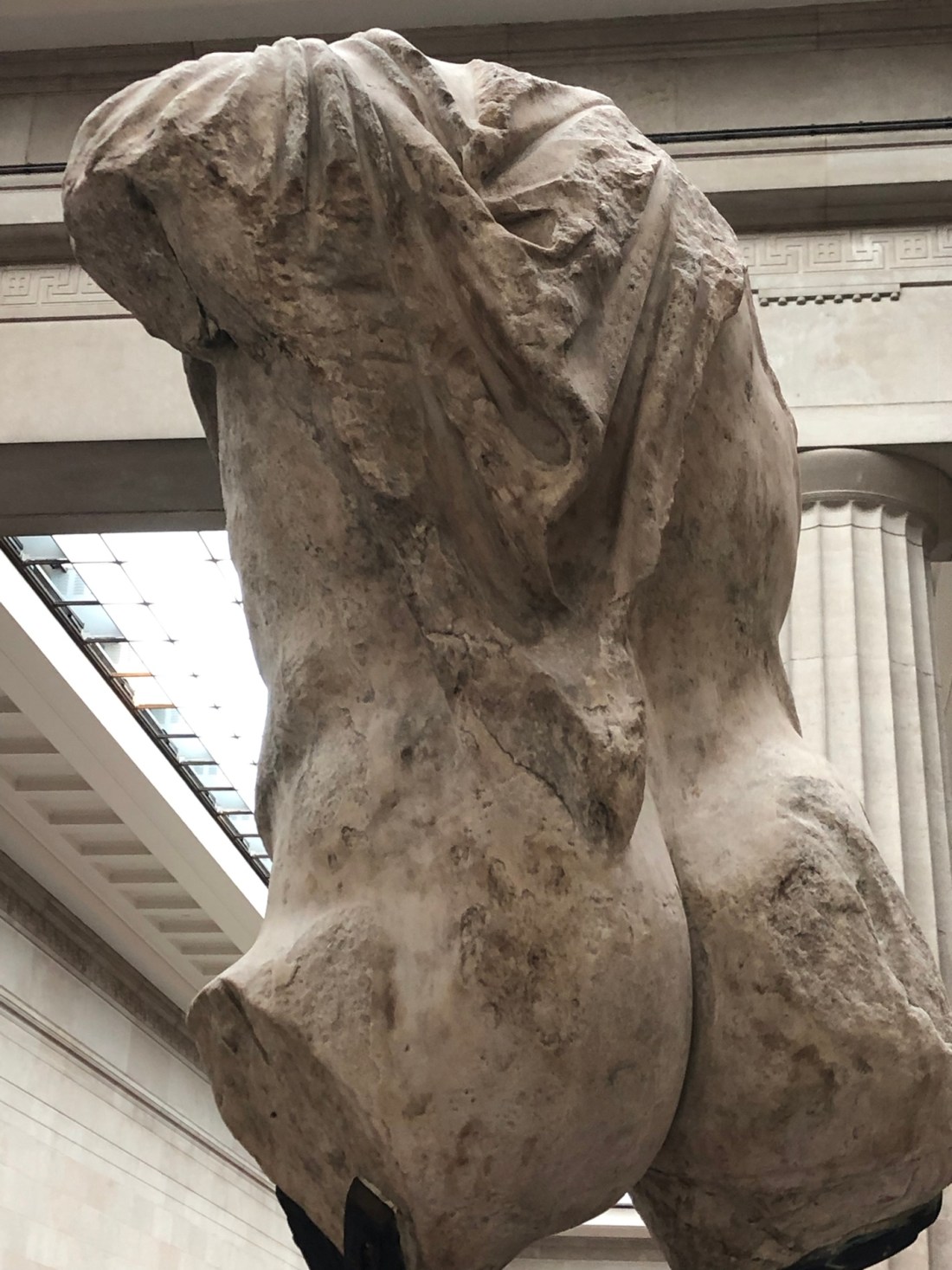

Sculptures from the pediment had suffered a lot of damage – and many were in pieces or simply missing. This sculpture is thought to be that of the girl is that of Hebe, cupbearer to the gods. She is obviously rushing to bring a libation to one of the gods!

There is also a statue of Hermès, from the west pediment. Only a portion of his torso remains.

The statue could only be seen by humans from the front, but the statue was a gift to the gods, who could see it in its entirety, so his short cloak is carved on the back.

Given the terrible condition of the sculptures left there that I witnessed when I visited Athens in the late 1970s, I can only appreciate that Lord Elgin, for whatever reason, and whether legally or not, preserved the marbles for us (and the Greek gods, if they are still around!) to enjoy today.

London has no scarcity of great museums, and the second one that I visited was the National Gallery. How to describe the miles of galleries and the beautiful paintings they include (about 2,300 of them, in fact)? There is no lack for paintings by Monet, for example, or Van Eyck, or Van Gogh or Klimt, or Vermeer, or Leonardo da Vinci, but the paintings to which I had the strongest reaction were by Rembrandt and by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (commonly known as Caravaggio).

This painting by Caravaggio is entitled “The Supper at Emmaus” and it was painted in 1601. It shows a very human moment: 3 men have sat down for supper together, with the innkeeper hovering behind. The man in the middle is blessing the bread, and the two others have just realized who that man is: Jesus, risen from the dead. You feel as though you are seeing the disciples’ reactions in real time: The disciples are so amazed, that one of them is bolting out of his chair, while the other has flung out his arms in such jubilation that his right hand is still moving.

In one gallery, hangs a self portrait by Rembrandt of himself at age 34, painted in 1640. It shows him as wealthy, successful and confident, with his life before him:

And, in the same gallery, almost opposite the first, his self-portrait at age 63, painted in 1669. He doesn’t spare himself – you see what life has done to him, and you know that it is almost over.

I stood before him for a long time.

Mary

London, England 9/18/19